All you ever wanted to know about the Kinder Scout Mass Trespass and the history of the Right to Roam campaign

If you visit us in our shop in Windermere village in the Lake District, chances are that while you are in the national park you will take a hike up one of the fells that the area is famous for. But while rambling and access to the great outdoors is a pursuit that many of us take for granted, did you know that the right to roam is rooted in working class radicalism and is still under threat today? In the 19th century rambling became a radical act – and with 92% of the English countryside still in private ownership and out of bounds to the public, remains so today.

The privatisation of our countryside

Land and class are inextricably linked in this country. In the 18th and 19th centuries a series of enclosure acts allowed landowners to consolidate common land and strip fields traditionally farmed by tenant farmers. In what was essentially a landgrab by the aristocracy, millions of acres were fenced off from the rural population that had traditionally farmed them. While the enclosure acts helped fuel the agricultural revolution, they were also abused by landowners: between 1786 and 1816 the number of landowners fell from 250,000 to 32,000. Our land was privatised, fenced off and under the control of a small number of rich landowners.

The enclosure acts also changed the social makeup of rural areas. At the same time as the enclosure acts were displacing tenant farmers, Britain was rapidly industrialising. Demand for workers for the new factories and “dark satanic mills” in towns and cities helped fuel the migration of labour from the countryside to urban areas.

The fight for the right to roam

Pressure for democratic reform grew throughout the 19th century as the working and middle classes campaigned for economic, political and social rights. Against this background of discontent, access to land also became a political issue. With increasing urbanisation came a disconnect with nature and the outdoors. After toiling hard in the mills and factories all week, should the urban working class not have the opportunity to enjoy the countryside for their health and wellbeing? The first demand for the right to roam was made in parliament 1884 with the Access to Mountains Bill. It was unsuccessful, but the fight for reform had begun.

An early victory in the Lake District

As well as parliamentary demands, grassroots activists were taking on the landowners by bringing the fight to the very land they wanted access to. Although Kinder Scout was the site of the most famous mass trespass in 1932, there were also earlier protests in the Lake District to protect access to one of our most popular fells. The ascent to Skiddaw and Latrigg from Spooney Green Lane in Keswick was closed by local landowners the Spedding family in 1887. In retaliation, over 2,000 protestors, including Canon Hardwicke Rawnsley, co-founder of the National Trust, and social reformer Samuel Plimsoll, member of parliament for Derby, trespassed on the Spedding land and gained the summit of Latrigg. The fight for access became national news and eventually the Spedding family were forced to open access to Latrigg. It was an early local victory in what was to become a long-running national battle for the right to roam.

10,000 march on Winter Hill

“Will yo’ come o’ Sunday morning, for a walk o’er Winter Hill?” asked poet Allen Clarke in the protest song in support of Bolton workers who had risen up against a local landowner and demanded the right to roam. In August 1896, Colonel Richard Henry Ainsworth decided to close a well-used track that crossed his land on Winter Hill. He had his gamekeepers turn people back and build a gate to show the way was closed.

Local people took umbrage at Ainsworth’s decision. Cobbler Joe Shufflebotham, secretary of Bolton Social Democratic Foundation, advertised a march up the disputed road. On Sunday 6 September 1896, about 10,000 people joined in the march as it progressed along Halliwell Road and up the hill. A handful of gamekeepers and police were waiting for them at the new gate but they were no match for the mass of demonstrators. The gate was smashed and the march continued. At their destination, on the north side of Winter Hill, the protesters drank the hostelries dry.

Despite the Winter Hill march being the largest mass trespass in English history, the protest wasn’t successful. Ainsworth won the resulting court case, despite Shufflebotham and the other leaders being represented in court by Richard Pankhurst, husband of suffragette leader Emmeline. Local people raised funds to pay the resulting fines, but the road remained off limits to the public for another hundred years.

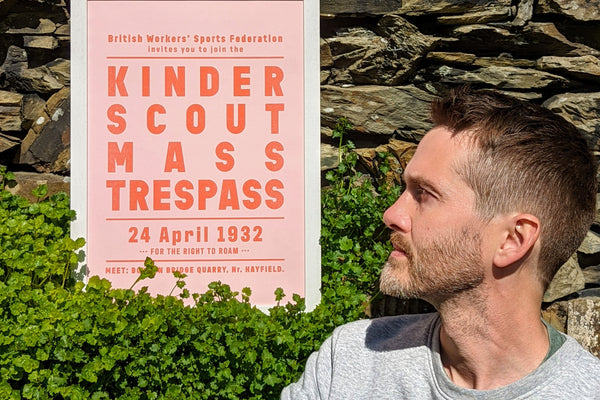

Kinder Scout Mass Trespass

By the 1930s and the Great Depression there was an even greater need for the urban working class to have free access to the outdoors for low-cost exercise. On 24 April 1932, around 400 working class ramblers took to the Derbyshire moorland to climb Kinder Scout. Led by 20-year-old Mancunian radical Benny Rothman of the British Workers’ Sport Federation, many of the group were also members of the Young Communist League. Their aim was to highlight the fact that workers from Manchester and Sheffield were denied access to vast tracts of land that were fenced off and only rarely used by its aristocratic owner for grouse shooting.

The protestors were met by gamekeepers and skirmishes broke out, leading to the arrest of six of the trespassers on charges of “riotous assembly”. Five subsequently served jail sentences of up to six months for breach of the peace and unlawful assembly. Their imprisonment made newspaper headlines and caused an outpouring of national sympathy. Calls for reform grew stronger and, with public opinion behind the campaign, the National Parks and Access to the Countryside Act was finally passed by the Atlee Labour government in 1949. Two years later the UK’s first national park – the Peak District, site of the Kinder Scout mass trespass – was created. A month later, on 9 May 1951, the Lake District was also designated a national park.

Why is the right to roam still important today?

It wasn’t until 2000 with the passing of the Countryside and Rights of Way Act by the Blair Labour government that the right to roam finally made its way on to the statute book. Partial right to roam was granted over about 8% of England, giving public right of access to land mapped as ‘open country’ (mountain, moor, heath and down) or registered common land. Yet 92% of the English countryside and 97% of rivers remain out of bounds for most of its population. This is not the case in Scotland and countries such as Norway, Sweden and Estonia, where everyone has the right to wander in open countryside, swim, wild camp and explore open spaces for the benefit of their mental and physical health. In England, over 90 years after the Kinder Scout Mass Trespass, the campaign for greater access to our countryside and the right to roam in our wild places continues.

We made this risograph print, dedicated to those protesters who fought for their right to roam at Kinder Scout and imagining posters inviting you to join the trespass. It's also available in black as a giclée print. England's largest mass trespass, at Winter Hill, is commemorated in this risograph print.